Cast of Characters:

The Scene:

Growing up in Marin Country, California, Setting out in the world at large, Becoming close friends with my step-mother Marget, and learning of her increasing fame, Creating this Website in homage to her.

Action:

It was a Saturday afternoon, in April, 1954. I was 151/2. My old man, Robert Brewster Freeman – then president of the San Francisco Art Director’s Club - was giving a poolside party for the visiting Los Angeles Art Director’s Club, and I had retreated to my lair, a converted chicken house where I had formerly operated a successful chicken business, selling door-to-door pan-ready fryers I raised from tiny chicks. Suddenly, a knock on the door. Hesitantly, I opened same, and my life changed forever. There stood my old man, with a gorgeous, tall, raven-haired young woman. “Marget, this is my son John. John, Marget Larsen”.

I was speechless. Never had I seen such beauty. Little did I realize that this woman was to become my step-mother. (Nor, of course, did I realize how famous she was to become. When I started this project in February, 2015, I was amazed to learn that there were over 100 "Marget Larsen sites" on Google alone, and that they still hand out the annual prestigious Marget Larsen Award for the best graphic design in advertising, and that Marget's works were to be seen in the Smithsonian, and that there is such a thing as the Marget Larsen Scholarship.) I, of course, fell instantly in love with her. This was somewhat unusual, even for me, because I was already desperately in love with Samantha, the beautiful 16-year old daughter of Will Connell, the editor of US Camera magazine, himself somewhat of a character. (He had a house filled with over 5,000 books, and he wore a cape all year long.) Marget skewered me with an appraising look, and we shook hands. The touch of her skin was electrifying. I don’t remember what I said, but I am sure that I mumbled something really stupid. I invited them in, and she nodded approvingly at my homemade draftsman’s table, where as an architect’s assistant, I was working on some plans for a house. After a few minutes, they took their leave, leaving me, in turn, in a state of inexplicable agitation. I knew that something important was about to change in my life, which turned out to be true, as several weeks later I had quit high-school, left home forever, and gotten a job as crewman aboard the 165-foot schooner Te Vega, about to set sail for Tahiti.

Fast-forward eight years. My having miraculously graduated from McGill Medical School, my dad had invited me to sail on the Swiftsure Lightship race in Puget Sound. To get there, we had to drive from San Francisco to Victoria, B.C. in his new sports car, zooming, along the way, to random towns in search of a guy wearing a Rainers Ale tee-shirt, who was walking to Seattle as part of an advertising campaign linked to the opening of the Seattle World’s Fair. My old man got busted driving 110 mph around a blind curve on the wrong side of the road. His attempt to fast-talk his way out of the ticket with the excuse “I didn’t want to clutter up the other lane, Officer” was memorably unsuccessful. I was not thrilled at the speed-crazed hazzards to my life, having just seen, during my last rotation in medical school, what happens to crash dummies when impacting a solid wall at only 25 mph. Upon our return (Marget and my old man were then living in a house built by Paul Allen on top of a hill in Kentfield, CA) and being informed of our exploits (a spinnaker blew out in a 50 knot gust on the way back to Victoria), Marget leveled the O.M. with a look that would shrivel a snake, and said simply “Oh, Bobby!”, a phrase that I was to hear with increasing frequency over the ensuing years.

During this visit to the West Coast, I encountered for the first time Marget’s place of business, a converted firehouse at 451 Pacific St. in San Francisco.

The ground floor had been converted into an art gallery, and it came replete with a big brass pole the fire-fighters used to slide down from the upper

floors. On the top floor resided another singular character, in the person of

Howard Gossage.

Gossage (my dad’s business partner in their

advertising agency Freeman and Gossage, Inc.) and I had quite a history. At age 13 one day I had answered the phone on the downstairs extension.

It was Gossage, calling for my old man.

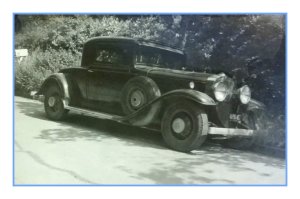

When my dad came to the upstairs phone, Gossage asked, in his characteristically booming voice, “Hey Freeman, how would

you like a 1932 Cadillac, for free?” (He had "sold" it [considering it bad luck] to a destitute artist-friend when a Gossage love-affair had turned sour, but the guy had never paid him for

it and

had abandoned it in the parking lot of the Tamalpais Theater in San Anselmo, CA, after a rear spring broke, where it had sat for a year before the cops

got onto him.) I immediately blurted out “I’ll pay you two chickens for it!”. Sold! Thus I became one of the few 13-year-olds

tooling around Marin County in a 1932 Cadillac Cabriolet named “Shadrack The Cadillac” with a rumble seat and golf-club compartment. Years later, I

helped get Gossage an experimental new drug for the treatment of leukemia when I was doing a post-doctoral fellowship with the Noble-Laureate

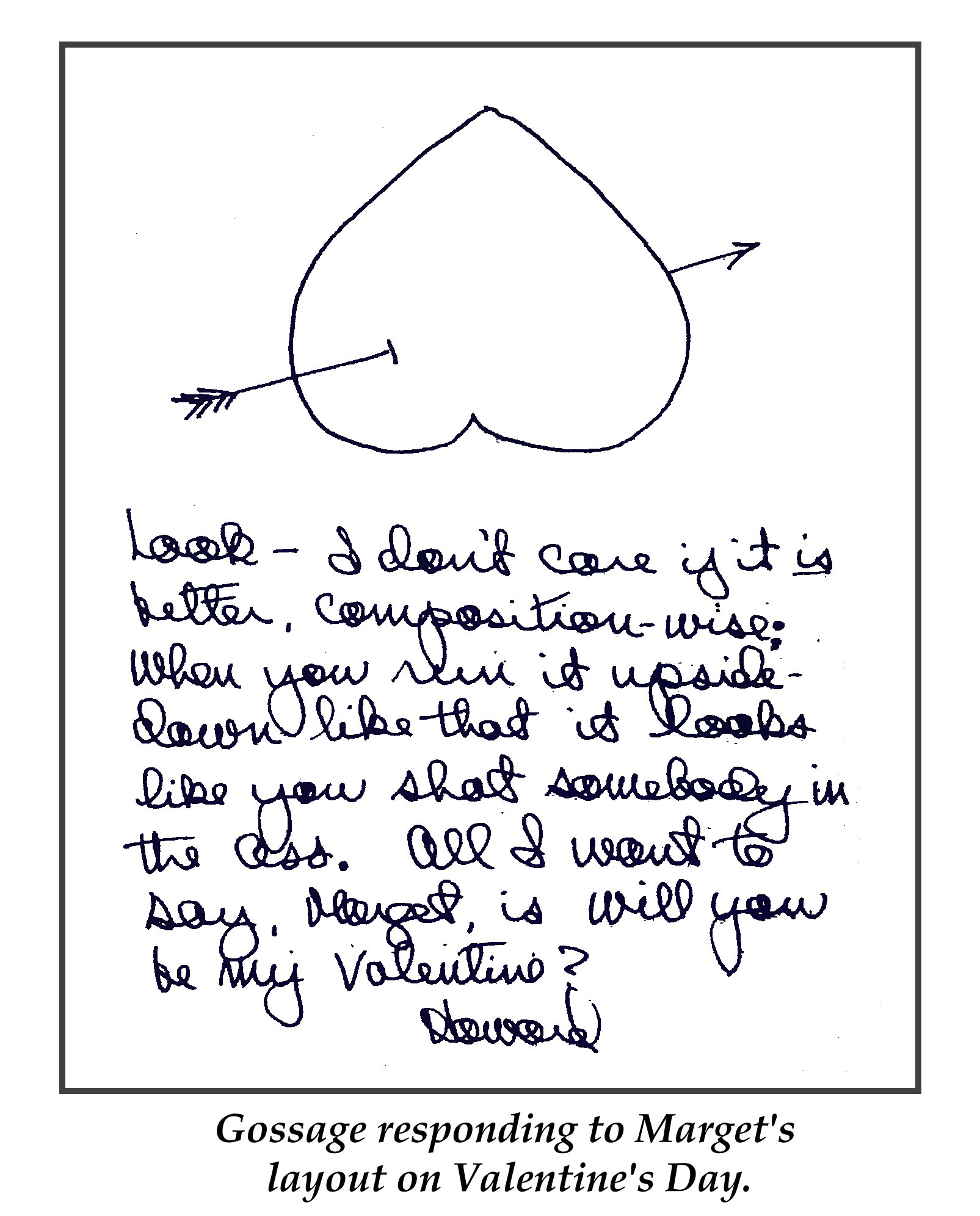

Sir John Eccles, whose standing I had shamelessly traded on to get my hands on a sample of the drug. Gossage wrote me a classic thank-you note in

which he stated “the moral: be kind to 13-year-old chicken salesmen.”

When my dad came to the upstairs phone, Gossage asked, in his characteristically booming voice, “Hey Freeman, how would

you like a 1932 Cadillac, for free?” (He had "sold" it [considering it bad luck] to a destitute artist-friend when a Gossage love-affair had turned sour, but the guy had never paid him for

it and

had abandoned it in the parking lot of the Tamalpais Theater in San Anselmo, CA, after a rear spring broke, where it had sat for a year before the cops

got onto him.) I immediately blurted out “I’ll pay you two chickens for it!”. Sold! Thus I became one of the few 13-year-olds

tooling around Marin County in a 1932 Cadillac Cabriolet named “Shadrack The Cadillac” with a rumble seat and golf-club compartment. Years later, I

helped get Gossage an experimental new drug for the treatment of leukemia when I was doing a post-doctoral fellowship with the Noble-Laureate

Sir John Eccles, whose standing I had shamelessly traded on to get my hands on a sample of the drug. Gossage wrote me a classic thank-you note in

which he stated “the moral: be kind to 13-year-old chicken salesmen.”

The “Firehouse”, over which Marget held sway in her office-studio, had become a magnet for all sorts of notable visiting firemen, including those

listed in the "cast of characters" above.

In my infrequent visits from Vanderbilt Medical School, I had met a number of these luminaries, and was impressed that they seemed to be drawn to the place by a combination of

Marget’s beauty and talent, and by a kind of artistic fervor in which advertising figured only peripherally. Gossage had become known as the

“Socrates of San Francisco”, and claimed to be more interested in getting at the "truth" to be had from a genuine quest for artistic value than

he was with making money while so engaged. This was a formative time for me, as I was involved in a conflict between style versus content. So,

evidently, was Gossage. My old man seemed to be more enthralled with style (typical attire: neatly turned out suit, spats, brightly colored neck kerchief,

and feathered fedora, while, as my son Russ Freeman of the jazz band “The Rippingtons” was later to note, I always seemed to be dressed like a bum).

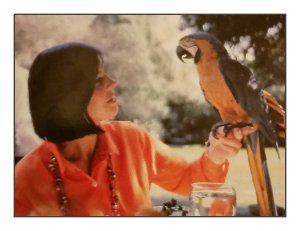

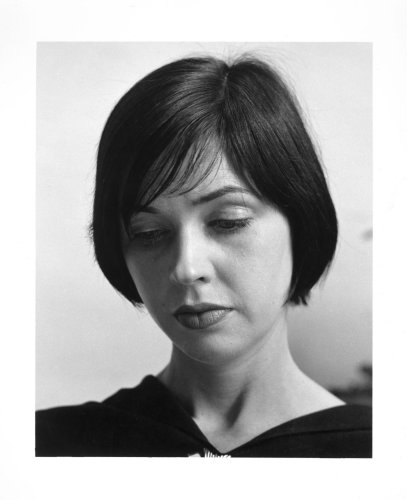

Marget, on the other hand, was enigmatic: you could not tell from her demeanor what was going on behind those intelligent, observant eyes. Did she

approve? Did she think that life was little more than a droll folly? Was she engaged in the present? Did she wish to be elsewhere? She was a very

private person, not given to talking about herself or attempting to claim the spotlight. (Although, the three princlples engaged in a lively

exchange of ideas, as seen at the right!) She was, as well, a very classy dresser, often making her own clothes out of fabrics that she had woven

herself on her giant loom, which took up most of the living-room.

She especially liked shoes. (The story has it that one day she came into Gossage's office wearing some very stylish pointed shoes. Gossage looked down,

then up, and said "Tell me, Marget, where do you get your shoes sharpened"?)

The “Firehouse”, over which Marget held sway in her office-studio, had become a magnet for all sorts of notable visiting firemen, including those

listed in the "cast of characters" above.

In my infrequent visits from Vanderbilt Medical School, I had met a number of these luminaries, and was impressed that they seemed to be drawn to the place by a combination of

Marget’s beauty and talent, and by a kind of artistic fervor in which advertising figured only peripherally. Gossage had become known as the

“Socrates of San Francisco”, and claimed to be more interested in getting at the "truth" to be had from a genuine quest for artistic value than

he was with making money while so engaged. This was a formative time for me, as I was involved in a conflict between style versus content. So,

evidently, was Gossage. My old man seemed to be more enthralled with style (typical attire: neatly turned out suit, spats, brightly colored neck kerchief,

and feathered fedora, while, as my son Russ Freeman of the jazz band “The Rippingtons” was later to note, I always seemed to be dressed like a bum).

Marget, on the other hand, was enigmatic: you could not tell from her demeanor what was going on behind those intelligent, observant eyes. Did she

approve? Did she think that life was little more than a droll folly? Was she engaged in the present? Did she wish to be elsewhere? She was a very

private person, not given to talking about herself or attempting to claim the spotlight. (Although, the three princlples engaged in a lively

exchange of ideas, as seen at the right!) She was, as well, a very classy dresser, often making her own clothes out of fabrics that she had woven

herself on her giant loom, which took up most of the living-room.

She especially liked shoes. (The story has it that one day she came into Gossage's office wearing some very stylish pointed shoes. Gossage looked down,

then up, and said "Tell me, Marget, where do you get your shoes sharpened"?)

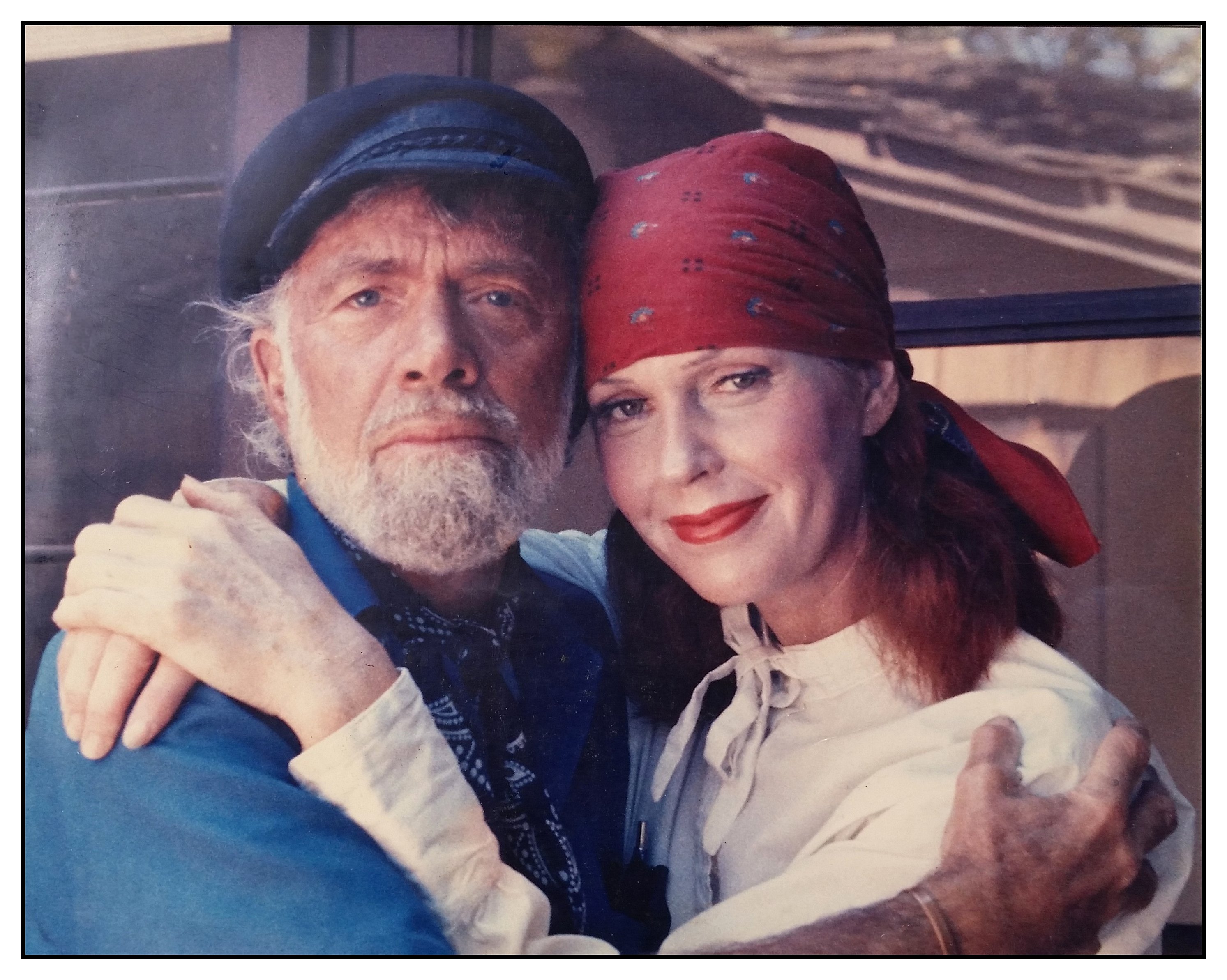

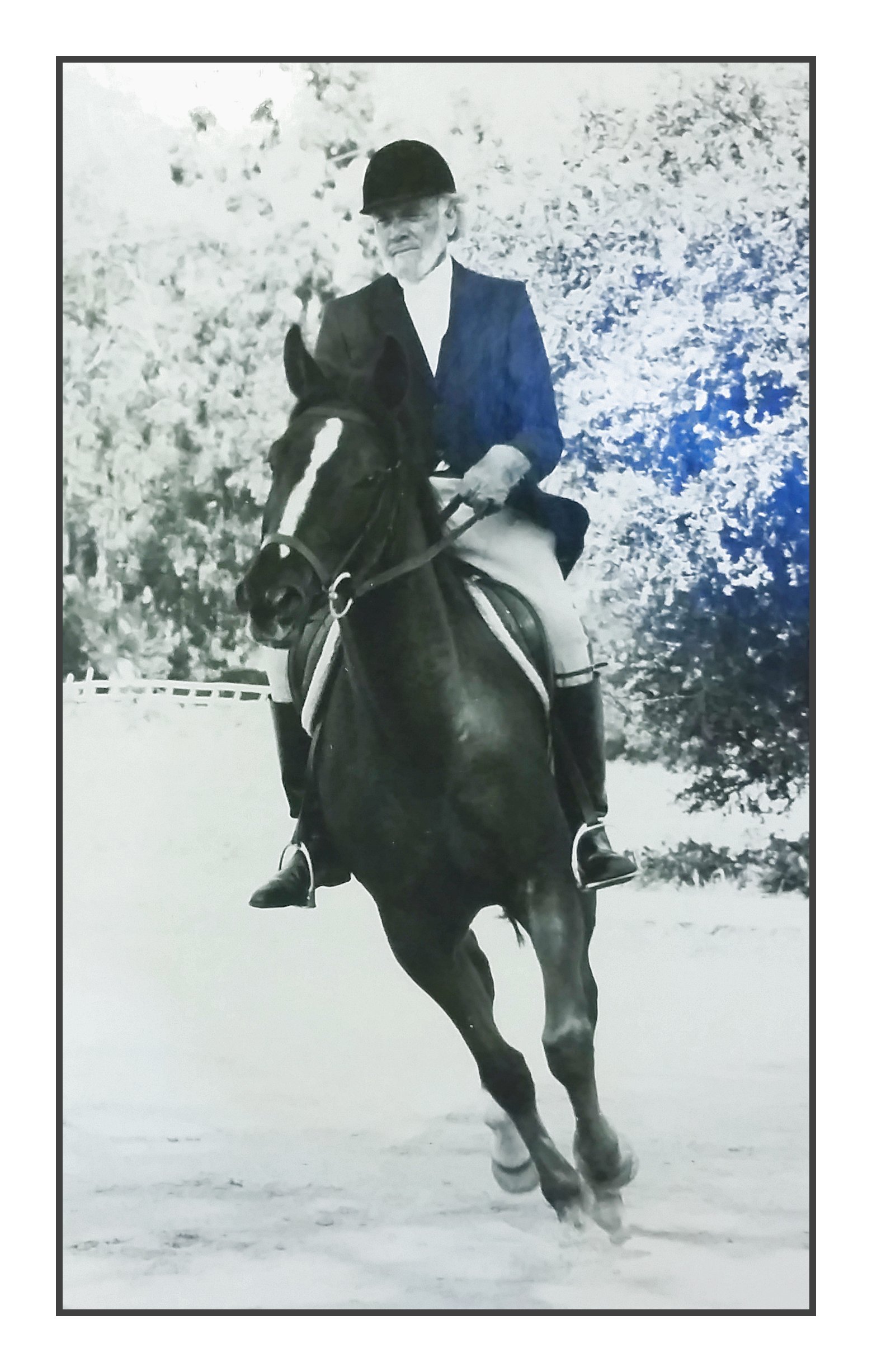

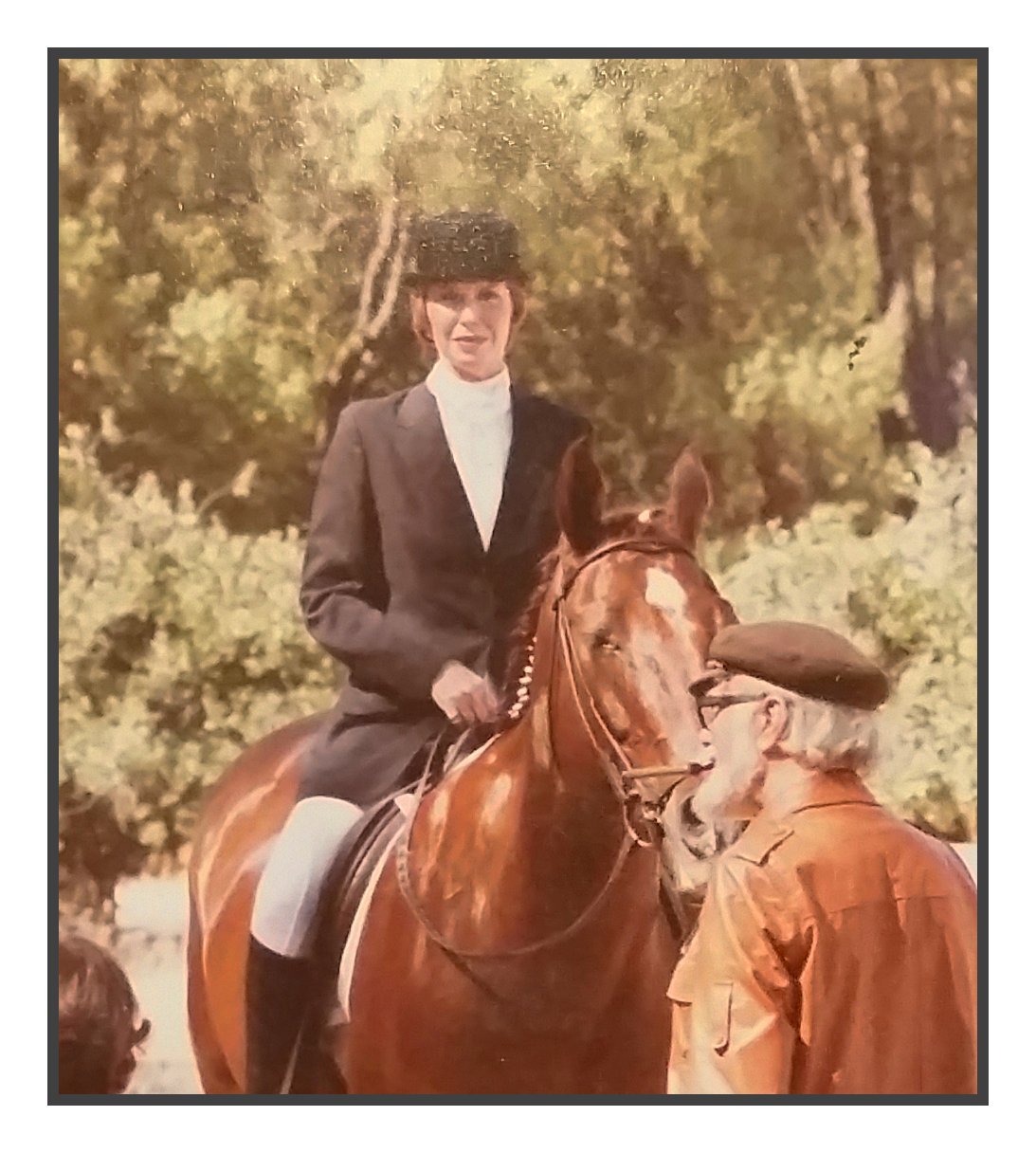

It took a number of years for me to get beneath the surface, and to become real friends with Marget. She was notoriously camera-shy, and the accompanying

photo of Marget and my father

It took a number of years for me to get beneath the surface, and to become real friends with Marget. She was notoriously camera-shy, and the accompanying

photo of Marget and my father

(which I took on the day my old man won the Northern California Dressage Championship on his quarter-horse “Moses” – Marget had lovingly braided the

mane of her stallion “Softy” for the occasion) is one of the very few pictures that I am aware that she ever allowed to be taken of her.

(which I took on the day my old man won the Northern California Dressage Championship on his quarter-horse “Moses” – Marget had lovingly braided the

mane of her stallion “Softy” for the occasion) is one of the very few pictures that I am aware that she ever allowed to be taken of her.

(Although, therein hangs another tale. The black-and-white pictures on this site were taken by the famous photographer ,

M. Halberstadt.

"Hal"

became my first official employer, when, at age 13 my father and I tooled over to Hal's San Francisco studio in Shadrack, and he miraculously hired me on the

spot to do all sorts of odd jobs [set up lighting, load cameras with film, make sun proofs, and other jobs]. He taught me practically everything I know

about photograpy,

which was a great asset to me when I was trying to get the color temperature and white balance right while taking the pictures of the original paintings

you see on this site. I am also indebed to his son,

Piet Halberstadt,

photographer nonpareil, for permission to use his father's photos of Marget.).

(Although, therein hangs another tale. The black-and-white pictures on this site were taken by the famous photographer ,

M. Halberstadt.

"Hal"

became my first official employer, when, at age 13 my father and I tooled over to Hal's San Francisco studio in Shadrack, and he miraculously hired me on the

spot to do all sorts of odd jobs [set up lighting, load cameras with film, make sun proofs, and other jobs]. He taught me practically everything I know

about photograpy,

which was a great asset to me when I was trying to get the color temperature and white balance right while taking the pictures of the original paintings

you see on this site. I am also indebed to his son,

Piet Halberstadt,

photographer nonpareil, for permission to use his father's photos of Marget.).

Marget was, in actuality, warm-hearted and caring. She was also amazingly talented, as the pictures on this site attest. They, in turn, represent a real treasure-trove. I found her original illustrations, after they had languished for many years in a portfolio case hidden away in the basement of their home, when I (as their sole beneficiary) was clearing out their estate after their deaths (Marget and my father finally got married, after living together for 25 years, shortly before her death in 1984. Their ashes are scattered together on the top of Mt. Tamalpais in Marin County, along with those of Marget's hero, Paul Klee.). She had a giant loom, on which she wove many beautiful tapestries. She also made her own jewelry, a center-piece of which was a large brass pendant that she wore frequently.

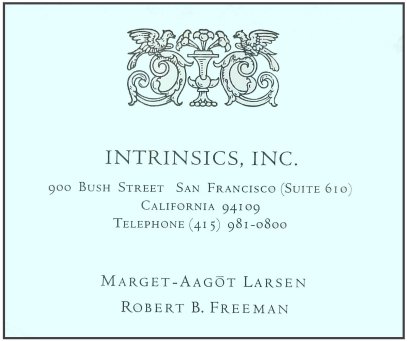

Sometime during the 1960's Marget and my old man started a spinoff business which they called "Intrinsics". (Their bassett hound, Dooty-Dooty, was the

official treasurer.)

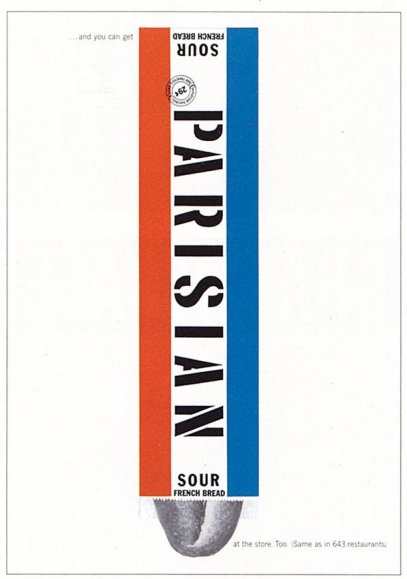

Intrinsics served as the vehicle for producing all sorts of amazing items, and it was during this epoch that they came up with the first silk-screened

sweat-shirts (the famous Bach, Brahams, and Beethoven garments that later sparked a whole new industry, although Pablo Picasso took great umbrage at his image

being emblazoned thereupon), the famous Scientific American Paper Airplane Contest, advertisements for merchandise containing pink air, and a plethora of ads for things

ranging from Dean Swift's Snuff Boxes, to Christmas box containers (which are still going like hot-cakes on E-Bay).

Sometime during the 1960's Marget and my old man started a spinoff business which they called "Intrinsics". (Their bassett hound, Dooty-Dooty, was the

official treasurer.)

Intrinsics served as the vehicle for producing all sorts of amazing items, and it was during this epoch that they came up with the first silk-screened

sweat-shirts (the famous Bach, Brahams, and Beethoven garments that later sparked a whole new industry, although Pablo Picasso took great umbrage at his image

being emblazoned thereupon), the famous Scientific American Paper Airplane Contest, advertisements for merchandise containing pink air, and a plethora of ads for things

ranging from Dean Swift's Snuff Boxes, to Christmas box containers (which are still going like hot-cakes on E-Bay).

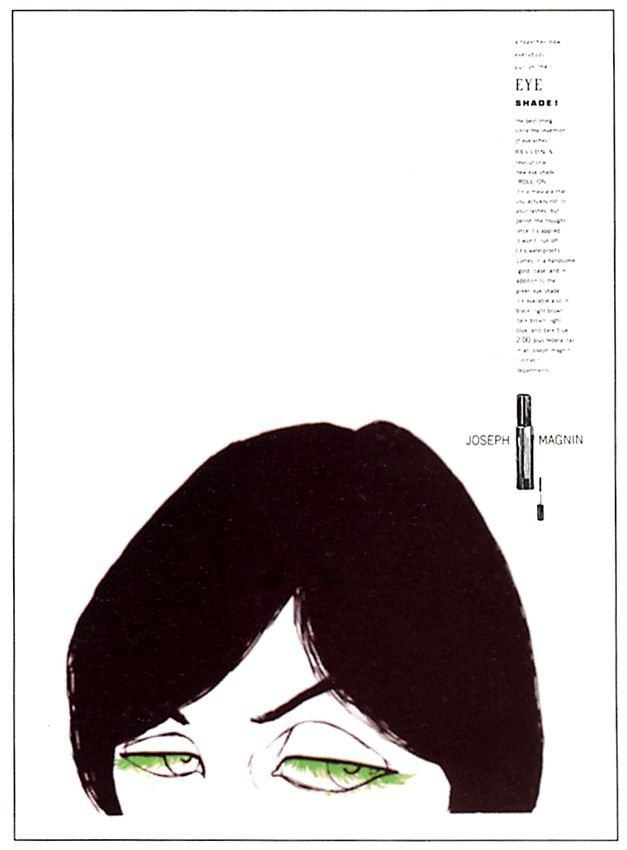

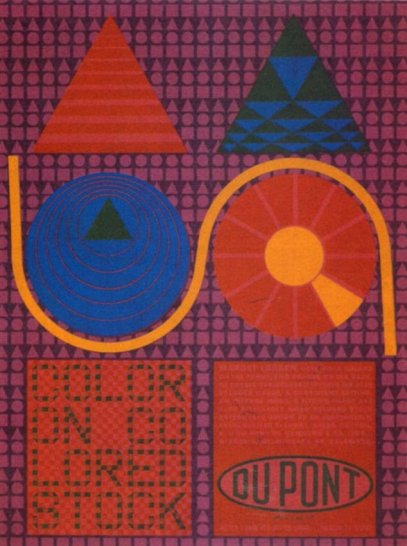

Marget really got into graphic design during this time (her favorite type-face was Centaur, in which her name above is set), and she designed the graphics for the San Francisco International Airport, for the Stanford University library, and for the Ghirardelli Square. They also pioneered in the Ecology Movement, helping to establish the Whole Earth Catalog, and contributing graphics and advertising towards the success of that venture, as well as for the Sierra Club. When programming the code for this Website, I had first to come up with a name for it. Unfortunately, some guy had already grabbed the name Intrinsics.com, and wanted $30,000 to sell it to me. That's why this site is called "New Intrinsics".

Why her career had to be ended so soon is hard to understand. But isn't it great that she happened at all! May Marget's spirit live on.

Dr. John A. Freeman, Marget's Step-Son

March, 2015